Isle of Man WW2.

Photo – Italian Internees

Agostino De Marco is in the front row on the left of the priest. In the top row third from the left is Alfonso De Marco and fifth is his brother Alessandro. Both are Agostino’s nephiews

The Italian community that had settled in Britain prior to WW2 was well integrated into society and although they had, by and large, retained much of their cultural identity and connections with their homeland, they had set up permanent homes and businesses here and their sons and daughters were born and educated in this country.

The historically friendly relations between the two countries and the pre-war freedom of travel and settlement meant that the older generation had not thought it necessary to acquire British citizenship.On June 10 1940, Mussoliini entered the war on the side of the Germans. An immediate round up began of Italians not possessing British nationality and Agostino De Marco, like many other Italians, was sent to the Palace internment Camp on the Isle of Man. In some cities, where there were large Italian communities, the arrests were carried out with some brutality and angry mobs attacked Italian homes and businesses.

The Andorra Star

Some internees were sent abroad by sea. On 2nd July, 1940, an unescorted converted passenger ship, the Andorra Star, carrying 1,571 German and Italian internees to Canada, was torpedoed and sunk off the west coast of Ireland, with the loss of 682 lives, mostly Italians. They had been prevented from reaching the lifeboats by barbed wire placed around the boat deck.The government was unrepentant. At the inquiry that followed, a government spokesman, the Duke of Devonshire, justified the decision to deport the refugees to the Dominions with the words: “It seemed desirable both to husband our resources and get rid of useless mouths and so forth.”

The Home Front

On arrival, Agostino contacted his family by post, A letter sent on 7 July 1940 to his son Giacinto is to tell him where he was – House 21 Palace Internment Camp Isle of Man, and his number – 578. He asked his sons to send cigarettes, tobacco, soap and a razor.

Agostino’s wife, MariaCivita was not interned but on 11 June 1940, she was instructed by Hove police to leave her home which was now in a restricted coastal area. MariaCivita could not read or write and spoke English with difficulty. Her sons protested about the decision to separate from them their elderly mother who was in poor health and who posed no threat to her adopted country but the authorities were insistent. Although her departure was delayed until 29 June, she then moved to 10 Chapel Road, Redhill.

With their businesses crippled by wartime restrictions, Geraldo now serving in the Hove fire service and Giacinto, with a wife and young family to support and about to be called up into the Army, this was a difficult time, particularily for my mother, Renee De Marco (Boulind). She had to look after two young children, the shop and often the animosity of some of her neighbours because of her Italian surname. Letters would be written to the local police, one complaint accused my mother of signalling to the enemy when she hung the washing up on the flat roof over the shop

Good People.

Next door to our house ther was a shop called Madam Hannah owned by a Jewish family called Lewis. They also lived above their shop. Their daughter Anita played with my sister Nina. They offered help to my mother, even money if, things got too tough.

Unofficial Leave

One night my father visited home unannounced with a stranger. My father was wearing full uniform with a rifle and Helmet covered in netting. I remember playing around with his rifle. I was so young that later in life, I thought that perhaps I had imagined this. Years later my father told the story.

One of my father’s duties involved acting as an interpreter fot Italian P.O.W’s attending court. Arriving in London one evening on esort duty during a heavy bombing raid, he had to find somewhere safe to take his Italian prisoner. He coulden’t take an enemy P.O.W. down to a public shelder full of people under attack. So they rushed to the nearest police station who refused to help as they much too busy dealing with the raid. As his prisoner was considered safe, he amd his prisoner simply caught the train to Brighton to visit his family and stay the night,

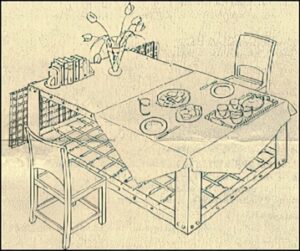

The Morrison Shelter – 19 George St, Hove

At the beginning of WW2, the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison introduced two types of bomb shelter for use at home for families who were unable to get to a public shelter, there were two types, the Morrison shelter made of heavy steel with a solid steel top and a space for a large mattress underneath. The top could be used as a table. I remember when young, visiting my grandparents in their shop at 19 George St, Hove just after WW2 and one was installed on the ground floor in the room behind the cafe. What a weird looking table, I thought.

During the war, I lived in Kensington Gardens and there we had a cellar accessable from the yard at the back of the shop. Lying in bed when very small, the siren sounded and my mother scooped me out of bed, wrapped in blankets and down we rushed – twice! the second time, leaning over my mothers sholder, I remember whispering in her ear ‘in and out like a little sprout’ .

Brighton Bombing

On the morning of May 25, 1943, the Luftwaffe attacked Brighton in the worst raid on the town of the war. One man has made it his life’s work to tell the story of that day. The raiders came and went in just six minutes – but they took a heavy toll,

Twenty four people died and over 130 were injured in the daylight raid. Over 150 homes were made uninhabitable, the Black Rock gasworks were set ablaze and the London Road viaduct was shattered. The raiders dropped 22 1000 lb. bombs, before going on to strafe Kemp Town, Black Rock and Preston Park with machine gun and cannon fire. David Rowland was eight years old on that day and has never forgotten what happened. He and a friend escaped death by a split second after the road they were crossing was machine gunned by a German pilot. “We heard a sort of pitter, patter noise on the road surface. This was the sound of the bullets hitting the road close to where we had just been standing.” he said.

Twenty four people died and over 130 were injured in the daylight raid. Over 150 homes were made uninhabitable, the Black Rock gasworks were set ablaze and the London Road viaduct was shattered. The raiders dropped 22 1000 lb. bombs, before going on to strafe Kemp Town, Black Rock and Preston Park with machine gun and cannon fire. David Rowland was eight years old on that day and has never forgotten what happened. He and a friend escaped death by a split second after the road they were crossing was machine gunned by a German pilot. “We heard a sort of pitter, patter noise on the road surface. This was the sound of the bullets hitting the road close to where we had just been standing.” he said.

Since then the former policeman has spent years researching the actual events of that day and talking to others who were there. One interviewee, Reginald Allam, then 13, had a lucky escape.A 500 lb. bomb passed through his house in Argylle Terrace before finally bringing down part of the viaduct which carried the south coast rail line. “We were bombed, the noise being like Satan hammering on the gates of hell. The noise was indescribably horrifying and I hope never to hear the like again..” said Reginald. Reg Fitch, then 14, was trapped in the debris of a bombed shop in Down Terrace. “Neither of us could move and extricate ourselves from the debris. The man wedged in with me was moaning and crying out repeatedly, ‘I’m dead, I’m dead’. For author David Rowland, the work of the past eleven years has been about proving that his childhood memories were real enough. He has one other mission – to see adequate civic recognition for the civilian casualties of war. Air raids killed 198 Brighton civilians during the Second World War. “You can look all around the town and there is no reference to the civilian casualties in Brighton – only in a book at St Peter’s Church. There is nothing on the war memorial, he said…

The Anderson Shelter – And My Uncle Fred

Fred and Edith Boulind, my mother’s aunt and uncle, lived in a cottage in a cul-de-sac leading off Worlds End Lane, Green Street Green, Orpington, Kent. And there am I, Frank (Agostino) De Marco standing next to him in front of his Anderson shelter which he has converted in to a useful shed. By the look of the roof some modification has taken place, no surprise as Fred was an active and capable handiman.

Silence is Deadly

When I was a small child I contracted whooping chough and bronchitus and was stuffed away in an isolation ward in Brighton. I can’t rember much except the ward had the windows open most of the time, there was no penicillin for civilian use then so fresh air had to do. Subsequently, recouperating in the countryside with a group of other children we were taken for a walk along a country road somewhere in Kent when the pulsating sound of an engine in the distance suddenly whent quiet. We were ordered to jump into the ditch beside the road and no harm was done. it was of course a V1 rocket.

Telephone House

North St./London Rd’

This was the nearest I came to real danger as a boy in Brighton during the latter days of WWII, I think it was in 1944 and my mother and I were looking into a shop window on the London Road face of Telephone House. It was a pet shop and in the window on a bed of sawdust there were several rabbits munching away. I was busy munching the fingertips of my wollen gloves when suddenly the air raid syren blasted out it’s hideous whine, loudly as it was on the roof right above us. My mother grabbed my arm and we ran around the corner and up North Road into the basement of Mence Smith. The room was packed and dead silence prevailed.As a child, I could only see upwards to the underside of the shop’s timber flooor and it’s supporting joists. Then the mighty bang. The bomb had exploded, where i am not sure but when we left to walk along London Road, the blast had shattered all the nearby windows and broken glass covered the whole road. I saw an injured man sitting on a dustbin his legs covered in blood. We were lucky that day.